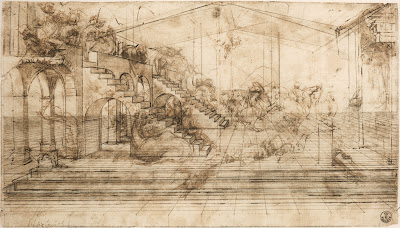

One Point Perspective: Adoration of the Magi

Adoration of the Magi, by Leonardo da Vinci. "The preparatory drawing for the “Adoration of the Magi,” the painting commissioned to da Vinci for the main altar of the monastery of San Donato a Scopeto near Florence, reveals the Italian genius’s innovative approach to art. His originality and mastery of perspective are evident in the magnitude of the illusionary space that he created. He drew the ground first, then a plan for the buildings and finally animated the scene with human figures and animals. Using a millimetric ruler, appointed stylus and very fine threads, da Vinci created the perspective grid to transfer the drawing on a larger scale as a painting on a wooden panel." From Share the Perspective of Genius: Leonardo's Study for the Adoration of the Magi, an online exhibition hosted by The Library of Congress.

Leonardo da Vinci's work is really wonderful to look at when learning about drawing, not only how to draw in perspective, but also how to build form with line, to represent volume, to diagram, to explain thoughts, and so on.

With regard to perspective, as it is represented in Adoration of the Magi, see the following observations: Notice vanishing lines lead to a central point, called the central vanishing point. There is only one vanishing point in this drawing, and therefore we call it a one-point perspective drawing. The point at which the central vanishing point sits is called the eye level, or horizon line. For those viewers who are are not familiar with thinking of space depicted in perspective, note how objects that are closer to the viewer are larger, and objects that are more distant appear to be smaller. Imagine standing on a long stretch of flat road. One can see the painted lines of the road converging and eventually merging at a place where the road seems to disappear. It is that point which is called the "vanishing point."

The Museum of Science has an online exhibition, Leonardo da Vinci: Scientist, Inventor, Artist, featuring Leonardo da Vinci. Below is an exerpt from one section, titled Artist:

"Leonardo got his start as an artist around 1469, when his father apprenticed him to the fabled workshop of Verocchio. Verocchio's specialty was perspective, which artists had only recently begun to get the hang of, and Leonardo quickly mastered its challenges. In fact, Leonardo quickly surpassed Verocchio, and by the time he was in his early twenties he was downright famous.

Renaissance Italy was centuries away from our culture of photographs and cinema, but Leonardo nevertheless sought a universal language in painting. With perspective and other realistic elements, Leonardo tried to create faithful renditions of life. In a culture previously dominated by highly figurative and downright strange religious paintings, Leonardo's desire to paint things realistically was bold and fresh. This call to objectivity became the standard for painters who followed in the 16th century.

No slouch when it came to the techniques of the day, Leonardo went beyond his teaching by making a scientific study of light and shadow in nature. It dawned on him that objects were not comprised of outlines, but were actually three-dimensional bodies defined by light and shadow. Known as chiaroscuro, this technique gave his paintings the soft, lifelike quality that made older paintings look cartoony and flat. He also saw that an object's detail and color changed as it receded in the distance. This technique, called sfumato, was originally developed by Flemish and Venetian painters, but of course Super-Genius Leonardo transformed it into a powerful tool for creating atmosphere and depth.

Ever the perfectionist, Leonardo turned to science in the quest to improve his artwork. His study of nature and anatomy emerged in his stunningly realistic paintings, and his dissections of the human body paved the way for remarkably accurate figures. He was the first artist to study the physical proportions of men, women and children and to use these studies to determine the "ideal" human figure. Unlike many of his contemporaries -- Michelangelo for example -- he didn't get carried away and paint ludicrously muscular bodies, which he referred to as "bags of nuts."

All in all, Leonardo believed that the artist must know not just the rules of perspective, but all the laws of nature. The eye, he believed, was the perfect instrument for learning these laws, and the artist the perfect person to illustrate them."

Amy Leidtke

Amy Leidtke